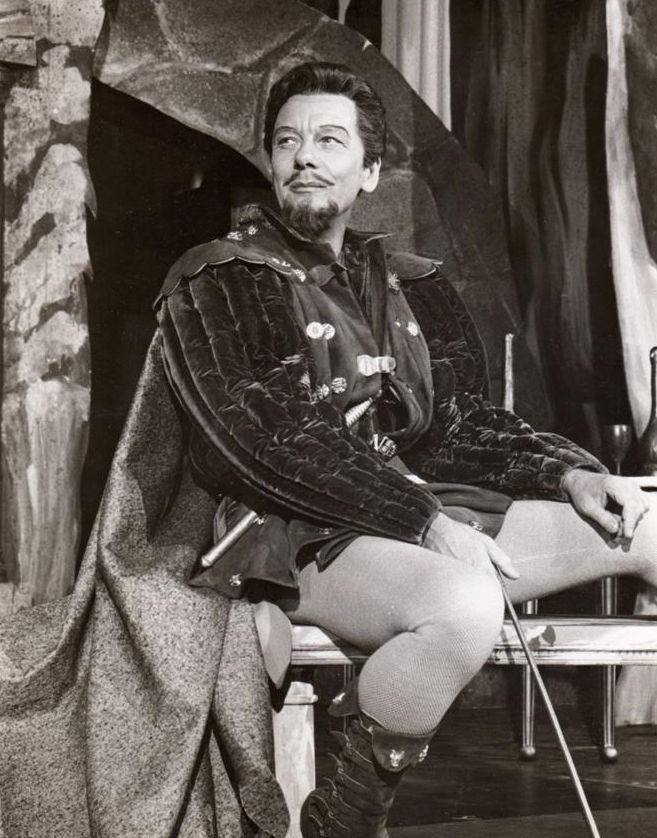

Best known today for his Oscar-winning turn as Dudley Moore’s butler in Arthur, Sir John Gielgud (1904-2000) was one of Britain’s most accomplished actor-directors and a world-renowned Shakespearean. He was also an excellent writer. His books Stage Directions and Acting Shakespeare offer witty, thought-provoking, and highly quotable content development advice for theatre artists and “creative types” of all kinds. And he’s at his most eloquent when discussing the essential ingredient to any creative process: collaboration.

Sir John Gielgud’s classic book Stage Directions is jam-packed with gorgeous gems of insight, especially in the chapter on The Importance of Being Earnest, in which he instructs the reader on how to get bigger laughs from an audience. While it may seem as though the book is intended only for theatre practitioners, his words and ideas are applicable to anybody in any profession.

For example, nothing’s more important than learning to play nicely with others:

First, I would say, you must learn to become a good partner. Just as in a game you are a member of a team, so on the stage you must try to provide the right support, balance and background. Learn how to listen…Be serious, devoted and disciplined, but do not take yourself too seriously. Nothing is more tiresome than an actor who pesters his colleagues with his own personal problems and theories about acting. Develop a thick skin for listening to adverse criticism, and a tolerance of your colleagues, even when you feel sure they may be in the wrong.

Here’s what he has to say about something that I struggle with every day:

It is always dangerous in the theatre to substitute scholarship and critical opinion, however brilliant, for contemporary instinct and fresh, vital imagination. I find it hard to work in detail before beginning to work with the cast of a play I am to direct, and I have never been altogether convinced that completely meticulous preparation beforehand can ever be entirely satisfactory. Until the day when all the participants meet together to begin the work, theory and planning, even on paper, can be no more than a daydream.

This paragraph is especially magnet-worthy:

The ideal director of Shakespeare needs to have remarkable gifts besides the fundamental qualities of industry and patience. He should, of course, have sensitivity, originality without freakishness, a fastidious ear and eye, some respect for, and knowledge of, tradition, a feeling for music and pictures, colour and design; yet in none of these, I believe, should he be too opinionated in his views and tastes. For a theatrical production, at every stage of its preparation, is always changing, unpredictable in its moods and crises. Every person concerned in it has a different attitude, a different problem…There must always be room to adopt an unforeseen stroke of inventiveness, some spontaneous effect which may occur at a good rehearsal and bring a scene suddenly and unexpectedly to life.

(Let’s replace the words “director of Shakespeare” with “content editor,” shall we? Oh, and switch out “theatrical production” for “the article your team is currently working on.”)

His book Acting Shakespeare is the product of a long and prosperous career (he was still playing King Lear at the age of 90). It’s a brief but potent read, introspective and at times brutally honest.

“I played in five or six productions of Hamlet over fifteen years — an extraordinary piece of luck for any actor. But many people said that my original performance in 1930 was the best because I had no idea that it was going to be good. When you get some sort of reputation behind you, it is much harder to live up to it and far more dangerous. Also, you are afraid of becoming a bit too pleased with yourself. The only thing that gives you satisfaction is to work with new actors around you and a new director who will not allow you to do many of the things you did before.” – Sir John Gielgud, Acting Shakespeare.

For my money, there has never been an actor more elegant, more inspiring, or more definitively old-worldly than Sir John Gielgud. I could listen to his voice for hours, but it isn’t merely because of its mellifluence — it’s what he did with it. Like all great artists, he strove to find the intelligence and nobility in the characters he played and remained an industrious student until the day he died.

Being totally real and weird and fallible, however, was also part of that artistic territory. Even so, his work stands alone — and speaks for itself.

As I mentioned in my previous blog post, creative thinkers are constantly looking to the past for inspiration and creative nourishment. Thank heaven we have part of this remarkable actor’s legacy preserved on film. If you haven’t watched Arthur — or the Brideshead Revisited miniseries — then I can’t possibly describe how much you’re missing out on. But that’s merely a crash course: Sir John’s subtle dignity will reveal itself as you dig deeper.

Now, go work on that document you’ve been avoiding. Don’t try to be a visionary — and stop overthinking it. Be spontaneous. Write it, get good feedback, don’t squabble over nonsense, make one or two revisions, click send and publish it. (#WhatWouldSirJohnDo)

Here’s to you, Sir John! (via GIPHY)

Haas Regen is the Managing Content Editor for 818 Agency in New York City. He’s also a theatre artist. He studied acting, directing, and playwriting at Brown’s MFA program.

WE CREATE YEAR-ROUND CONTENT AND LEAD GENERATION CAMPAIGNS FOR B2B TRADE SHOWS, CONFERENCES, AND GROWING COMPANIES. GET IN TOUCH.